The Birth of the Jersey Surfboard Club

Surfing in Jersey first became popular in the 1920s after a well-travelled Jerseyman, Major Nigel Oxenden tried to replicate what he'd seen on a trip to South Africa and Hawaii. He introduced belly boarding to Jersey forming the Island of Jersey Surf Club with its HQ being the 'Green Hut' , which still stands in the Bay next to the Watersplash today. Records from the Oxenden family Archives and eyeball accounts from surfers of this era state that Archie Maine was one of the first stand up surfers from the late 20's.

Strange as it may seem, the Jersey Surfboard Club story begins in a London cinema in 1958.

Lifeguards Shorty Bronkhurst, Bobby Burdon and Cliff Honeysett found themselves in the gloom of a British winter, and felt homesick for their native South Beach, Durban. The three of them had already decided that coming to England had been a mistake – they’d just registered to emigrate to Australia.

But a trip to the movies was to change all that. The short film supporting the main feature was made by Jersey Tourism, and showed footage of nice-looking waves rolling into St Ouen’s Bay. They were so stoked, Bobby and Cliff jumped on the ferry from Weymouth to check out the Island, and returned to tell Shorty that they’d all landed jobs for the summer at Parkin’s Holiday Camp, situated on the Island’s north coast.

Once there, they set about building some 14ft surfboards - allegedly out of the flooring at the holiday camp - and tested them out at Plemont Bay, the nearest local break. But there was better surf on the west coast, and it was there that they wowed the locals by standing up as they rode in on the waves.

Hospital radiologist, Dr Peter Lea, and his friend Charles Harewood, the Chief Pharmacist, were so impressed that they ran up and asked to have a go, and so the seeds of the Club were sown. The South Africans soon left Parkin’s and went to work for Harry Swanson at the Watersplash. Harry didn’t hire them just for beach safety - they did odd jobs for him as well - but there had been a spate of recent drownings, and he realised that the presence of lifeguards would make the area safer, and therefore more popular. So successful was this strategy that they were soon joined by Dennis Everett, Kevin McCann and Bill Lavarack.

Peter Gould was one of the first to meet the South Africans, because the Victoria College swimming team used to train in the pool at Parkin’s Holiday Camp. “One of them built a board about three feet wide, like a surf ski, and about eight to ten feet long.” he says. “It was a squat, ugly-looking thing. He let us take it out and we’d stand up on it, which was absolutely revolutionary - we’d only ever used belly- boards before then.”

Local surfers soon began making their own boards out of plywood, based on the South African designs. Besides weighing in at 50 or 60 lbs, these “cigar-box” monsters were hollow and prone to fill up with water, with a cork to let it out. “That was your prize possession,” said the late Tommy Bates, an early board maker and pioneer. “You’d be running round going: ‘Who’s pinched my cork?’”

“They had no leash,” says Peter Gould, “just a big iron hoop on the back to catch them when you fell off. When you missed it, which you generally did, the thing would come in sideways, cutting a swathe through the belly- boarders like an eighteen foot Boadicea-type scythe. That’s when they started the laws limiting surfing areas, because a lot of local people with belly-boards didn’t want to get their heads caved in!”

With belly-boarders demanding safe areas to swim, and the States of Jersey getting involved, the stand-up surfers decided they had to band together. The idea of a club was formed, and in August 1959 it was officially inaugurated, with Peter Lea, the driving force, as president, and Charles Harewood as Treasurer.

The South Africans at the Splash weren’t the only lifeguards on the beach. Pat McGarry had already set up a volunteer service, called the Jersey Life Guard Club, and in 1958, they brought in some Australian lifeguards - the first of whom was Jim Wilson - with a grant from Jersey Tourism. Based at El Tico, they helped train the local lads who belonged to the JLGC, who in turn helped them on their patrols. JLGC members included Richard and Tom Bates, Mick Ems, Ian Harewood, Barry Jenkins and Tony Whiteman.

“One of the States Lifeguards, Dave O’Brien, was ex-army, and he had us marching up and down the beach,” recalled Tom Bates. “We practised all summer, towing belts out through the surf, and became very strong swimmers. We also did chariot races when there was a surf carnival at Greve de Lecq,

History of Jersey Surfboard Club - Gordon Burgis

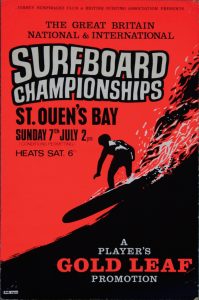

Surf contests were massive events in Jersey in the 1960’s. Crowds of ten thousand or more would pack the sea wall to watch locals thrash it out with international surf stars, not for the mega bucks on offer today – they did it for 200 fags, an embossed lighter and the glory of lifting a trophy!

Tobacco advertising was still socially acceptable, and the backing of John Player cigarettes lent the events at St Ouen’s a cachet which other venues couldn’t match. “It was impressive to have a recognised brand like Gold Leaf sponsoring it – it sounds odd now, but back then it added glamour,” recalls 1970 British Champion, Roger Mansfield.

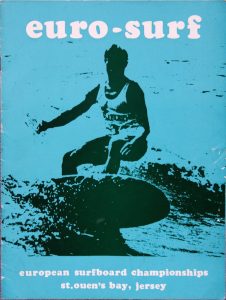

The list of events held in Jersey in those early days is staggering: the first ever UK regional event in 1963; the first British Championship in ‘64; and a string of other national and international contests, culminating in the first two European Championships in 1969 and 1970.

The driving force behind these prestigious National and International contests were JSC stalwarts Davids Grimshaw and Beaugeard, and the late Mike Ferguson. And to cap it all, by 1969, Miss World was presenting the prizes!

With looks that literally stopped traffic, 19-year-old Penny Plummer’s presence at the ’69 Euro’s was the icing on the cake for the JSC. A librarian from Sydney who listed “surfriding” as one of her hobbies, she was under exclusive contract to John Player, the contest sponsors, and was in Britain as part of her reigning Miss World tour. “She certainly brought in the crowds,” recalls Grimmo. “You couldn’t get down Jubilee Hill!”

Jersey had become the Mecca for competitive surfing in Europe, and by so doing had earned itself a place on the world surfing map. Names like Puppy Dog Paton, Lovedog McMenace and Carl Corillo would appear in the list of heats, and many of them would stay on in the Island to enjoy its world-renowned hospitality.

“The craic was fierce in those days,” says Grimshaw, who was Secretary of the JSC in the 1960’s. “People came here partly for the kudos of competing, but also because they had a bloody good time.”

And, it should be added, because the events were superbly managed. “Back then, we’d never seen anything like the organization we saw in Jersey,” says Roger Mansfield.

David Grimshaw

More than anyone, it was David Grimshaw who was responsible for this phenomenal success. “I spent my life writing letters,” he says modestly. A keen surfer himself, “Grimmo” not only instigated and organised the Jersey Surfboard Club but also the British Surfing Association, being appointed its first president in 1966, and was instrumental in getting Jersey surfers invited to three World Championships. In 1983 he became Secretary General of the International Surfing Association, and was on the executive committee organising the World Championships for ten years.

It is doubtful that anyone else could have achieved such success, because coupled with his organisational skills, Grimmo’s over-riding attribute is his popularity, which stems from his sheer sense of fun. Whether it be passing round a bag of toffees laced with sheep dung, or building a kitchen across Barry Jenkins’ drive,if there was a prank being pulled, Grimmo was probably at the centre of it.

In 1983, he was made Honorary Life President of the JSC, an honour which for him was the proudest moment in an amazing and illustrious career.

The First European Championships

The ’69 European Championship was probably the high-water mark of the Jersey contest scene. Not only was Miss World the guest of honour, but local boy Gordon Burgis beat the reigning British Champion, Rodney Sumpter, in a nail-biting final dubbed “The Battle of the Giants”.

Sumpter was renowned for his ability to make poor surf look fantastic.

“It was the way he walked the board,” remembers Grimmo. “He could make any wave look good.” He had won two British titles while Burgis was away travelling, and was regarded as the man to beat. But on that day, Gordon Burgis re-asserted himself as the undisputed king of European Surfing.

Like all the events organised by Grimmo, the contest was a triumph. But there was one little unforeseen problem with the catering!

“The visiting surfers had been told they all had a voucher for the buffet,” explains David Beaugeard, then club president. “There were guys from all over, from England, from France - they didn’t have much money, we’d put em all at the camp site - and suddenly there was all this food! So as soon as the presentation was over, they went straight to the Watersplash and just devoured everything in sight.

“By the time Clarrie Dupré and Miss World and all the dignitaries got there, there wasn’ta thing left. It was just like the locusts had been!” remembers Grimmo. “Harry had to go downstairs: ‘We’ll have to g-get them some more!’ I’ve never seen tables emptied so quick! They ate for a week!”

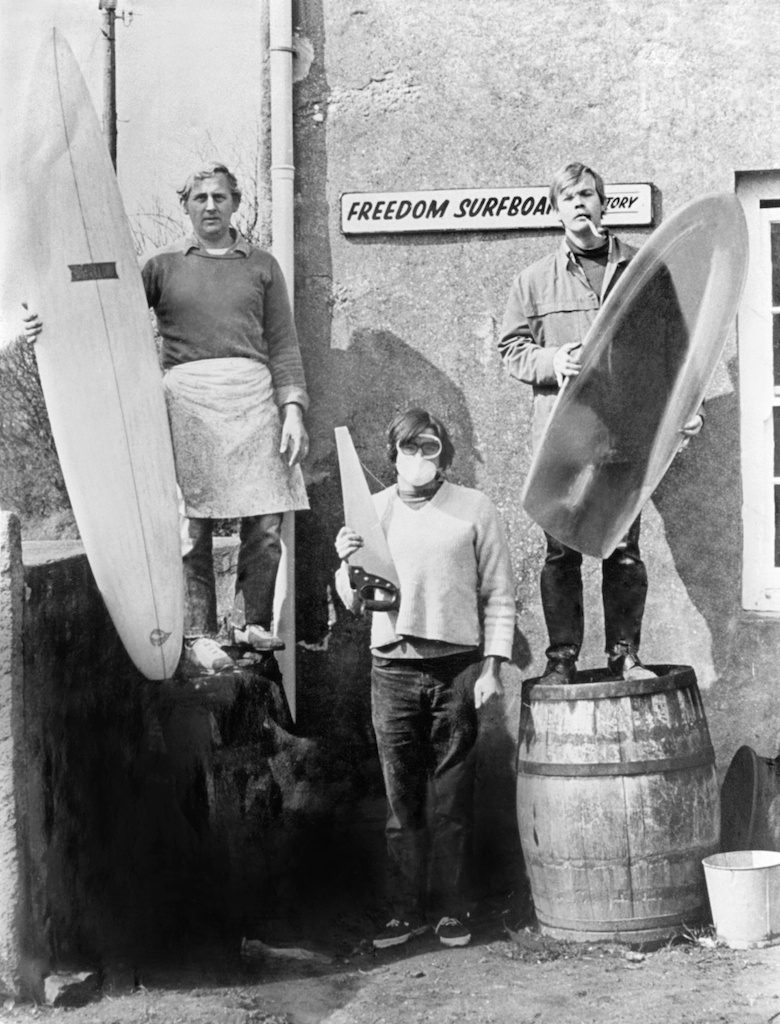

Birth of Freedom Surfboards

If Gordon Burgis was the king of Jersey surfing in the 60s, his successor for the following decade must surely be Steve “Honky” Harewood.

Honky - he says he got the name from the effect his vegetarian diet had on his digestive tract - was founder and chief designer of Freedom Surfboards, the biggest surfing business in Jersey.

By exporting boards throughout Europe, he was a major influence on the sport right through the 70s and 80s. He was also a great competitor, gaining numerous top three placings in Great Britain and Channel Island Championships from 1962 onwards, as well as winning the 1994 European Veterans title.

Freedom Surfboards started out - and indeed continued - as a labour of love.

“You just feel compelled to do things regardless of the consequences,” says Steve. “I just loved it, I didn’t even think about the money.

“I started Freedom in 1969 on my own. I came back from America with long hair, a couple of Doors albums and a bit of stash, and I triedto think of the name for the ideal surfboard. I thought it would have to have total freedom on a wave, so that’s why I chose the name.” Steve was the creative force behind the business. But it might never have taken off without the help and business brain of Barry Jenkins.

Both men had been in the team which went to Puerto Rico in 1968, and from there had gone off on their own separate trips around the world. On his return to Jersey, Barry bumped into Steve on the beach.

“I didn’t have a trade or a business or anything - I was just humping cement around as a labourer,” says Barry. “Then I bumped into Steve and he was looking for a business partner. He had a garage at La Pulente and it was very, very small.”

“We made 15 or so boards the first year, and everyone went, yeah, we want these boards. But space in my Dad’s garage was limited, and that’s when Barry came up and said: ‘We should do this properly,’” says Steve.

“Steve was very clever technically but he had no business skills,” says Barry. “He needed to raise some money, and although I didn’t have any myself, I was able to borrow some. So I got the funds together and we set up a factory at St Ouen, the Farm.”

While Barry was setting up the factory, Steve went back to California and worked for Dewey Weber for six months, to get some more experience on the latest shapes and manufacturing expertise. In the meantime, Barry and Tommy Bates were turning out fibre glass reclining chairs for swimming pools to make some cash.

“They’d set the place up for fibre glassing, and when I came back I started shaping,” says Steve.

This first factory was behind Honky’s Dad’s house, opposite the Barge Aground, but the Planning Department didn’t like it.

“It was just a farm barn, we had no planning permission for a commercial enterprise in an agricultural building. So in1973 we went to Ordnance Yard at the Weighbridge - which was a nightmare,” says Steve.

Barry continued to make boards with Steve until about 1972, when he started to suffer from severe arthritis. He eventually restored some of his fitness by swimming and body surfing, but Barry’s glassing days were over.

Around this time, the Guru Maharaj Ji became a big influence at the factory.

“I was hooked into “Guru Fever”, which seemed to be all the rage in certain circles,” says Steve. “Being a charitable person, I gave jobs to all the devotees - Sas Scobie, Peter Hansen, Tom Shapespeare (none of whom surfed) plus Don Thompson and Bobby Male (who did). We started our day by meditating under blankets for half an hour in the show room.

“My belief in employing followers was that sincere spiritual beings would make perfect employees - how wrong can you be! The general philosophy was that there was a universal force that we could tap into that ordained everything, and nothing in the material world really mattered - including surfboards!

I remember this guy completely ruining a customer’s board and me shouting: ‘How the f*** did you do that?’ He went into a long diatribe about how mistakes are actually meant to happen, and are all part of the universal flow, and that the customer must have attracted the mistake into his life!”

There followed a couple of difficult years for the factory, with attention to detail seriously lacking and pretty poor finishing's. “Eventually, I came to my senses and hired only surfers, who showed a far keener interest in the finished product, and were also craftsmen.”

Some of the younger crew were also interested in the Guru, but they didn’t always get what they expected!

Dave Ward was living in Midvale Road, and thought he’d pop round to a meditation evening because it was nearby. “My sister says to

me: ‘Are you not going to eat tonight?’ and I said: ‘No, I’m going round to the Satsang, just around the corner,’” remembers Dave. “Being a really stupid Yorkshireman, I thought the Satsang was a restaurant! But it wasn’t, I was going round to Honky’s, where they all sat round in the room with candles and prayed! I was absolutely starving!”

Steve Carter didn’t expect to get fed, but he still didn’t know what to do, because everyone was too blissed out to explain.

“Bobby Male invited me to a meeting. “It was in a basement flat in Rouge Bouillon. We all took off our shoes and sat in a circle, chanting. I just sat and watched and chanted along with them. Then finally someone came along with a tray with a candle on. I was sitting at the end so they came to me first, and not knowing what to do, I reached out to take it from the girl. She wasn’t letting go, so we had a bit of a tug of war with the tray, with me trying to take it and her not letting go.

“Everyone was in a tranced out state of bliss and not speaking, so I thought: ‘Well, she obviously doesn’t want me to take it, so what else do you do with a candle? I must be supposed to blow it out! So I did. This caused a stir amongst the blessed ones: ‘Oh, no! He’s blown out the Divine Light!’ Luckily Bobby’s wife stood up for me and said it was my first time, so I was forgiven. I never went again.”

In 1976, board production moved to Coin Varin, in St Peter, where it stayed until 1985. At the peak, they were making about thirty boards a week, but it was a seasonal business in those days.

“We’d make three or four hundred boards a year, because no one bought them in the winter in those days,” says Steve. “The factory used to virtually close down for the winter.”

In the meantime, he was busy pushing the limits of design, with some experiments being more successful than others.

“I read this idea about air bubbles lubricating the underside of the board. So we put a sort of mouth on the front of the board to suck the air in, and connected it with a hollow tube inside the board, so it would suck air through the top and the air bubbles would come out underneath. The trouble was, it kept catching the nose and the bloody water went down the front. I surfed it for a few days, to see if it actually was faster than a normal board, and it worked okay, but if you did any manoeuvres you’d catch the nose and it filled up with water!”

By now, Freedom was a brand with international cachet, partly due to Steve’s design skills, but also due to the factory’s self-styled “spray guy”, Jon Hetherington.

Buyers would come from the UK specifically so they could get hold of boards that he’d worked on, and surf shops in France vied with each other to grab the ones with the best designs.

“You knew if you stopped at a shop in France they would always take the boards with the fanciest paint-jobs,” says Jon. “When we got our first DayGlo paints in from the States, the French shop-owners went mad for them - they knew those boards would just fly out of the door.”

A graduate in graphic design, Jon had already spent two seasons in Biarritz, airbrushing boards at a small factory up-river from La Barre. In the late 1970’s he came back to Jersey and joined the crew at the Freedom factory. “Steve approached me to work at the factory. Bobby (Male) had been doing the spraying until then and he’d also been blowing blanks for a few years, using these big concrete moulds built by Dave Ward.

As well as building the moulds, Wardy worked at the factory as a sander. But the relaxed attitude just didn’t fit his way of working.

“I’m definitely an eight o’clock man and that’s just how I work,” says Dave. “But I was the only one in at eight o’clock. The other boys tended to surf until ten and then come in, so for two hours most days I didn’t have any boards to be sanded, because nothing was ready. It just didn’t suit me. Also, I sometimes used to get paid in surf boards. But I was staying with my sister, and I couldn’t skip on my rent. She’d say: ‘I can’t eat a surf board, can I?’”

“We’d always get paid eventually,” recalls Jon Hetherington. “But sometimes you had to wait until the end of the season, or until he’d sold a shipment of boards.”

Getting goods to market was often a challenge as well.

“We once worked all night to finish a batch of boards destined for France,” says Steve. “We finally finished at about 5 am and loaded them onto the van just as the sun was rising. Time for a well-deserved cup of tea and enough time to relax on the factory roof before setting off to catch the 9 am ferry. Needless to say we fell asleep and missed it!”

Being late for the ferry was an occupational hazard. “Another time we hit traffic at La Haule, and knowing we would literally miss the boat if a miracle didn’t happen (we had to clear customs before the weekend) Sas took the initiative and swung the Transit down the slip and onto the beach - luckily the tide was out. We raced across the beach with our hearts in our mouths, through soft sand and hidden obstacles, up the slip at West Park and guess what - we made it! Miracles do happen!”